Frank Underwood, Comcast and the FCC

If you haven't watched the second season of "House of Cards" (or, gasp, any of the show), be glad that Netflix just paid Comcast a lot of money to ensure that will be able to continue to do so in high-definition and 4K.

For those who are uninitiated, "House of Cards" is a show produced and distributed by Netflix; it is a take on a British show of the same name (1990). Our American version features Kevin Spacey and Robin Wright as Frank and Claire Underwood, two conniving, and deceitful Washingtonians and their ultimate quest for vengeance, power and glory stemming from those who betrayed Frank in the first episode (more about the show can be read here and watched here).

This isn't a post about the show, but more chatter about the overall way that we are (globally) consuming content (in all forms) and how providers, creators and consumers are all intertwined (for good, and for evil).

With the recent news that Comcast plans to purchase Time Warner Cable, as well as the net neutrality controversy in which Netflix agreed to pay Comcast for better bandwidth for content delivery to Comcast subscribers, I believe that the dam is beginning to crack, indicating a sea change in content delivery protocols, methods and laws for delivery across all channels and platforms.

Some might welcome this change as a necessary evil for the overall increase in quality, speed and content that the public seems to clamor for (especially in 4K). Others will most definately see this as an affront to net neutrality and an overreach by a (despised?) major corporation that has begun to acquire content providers such as NBC.

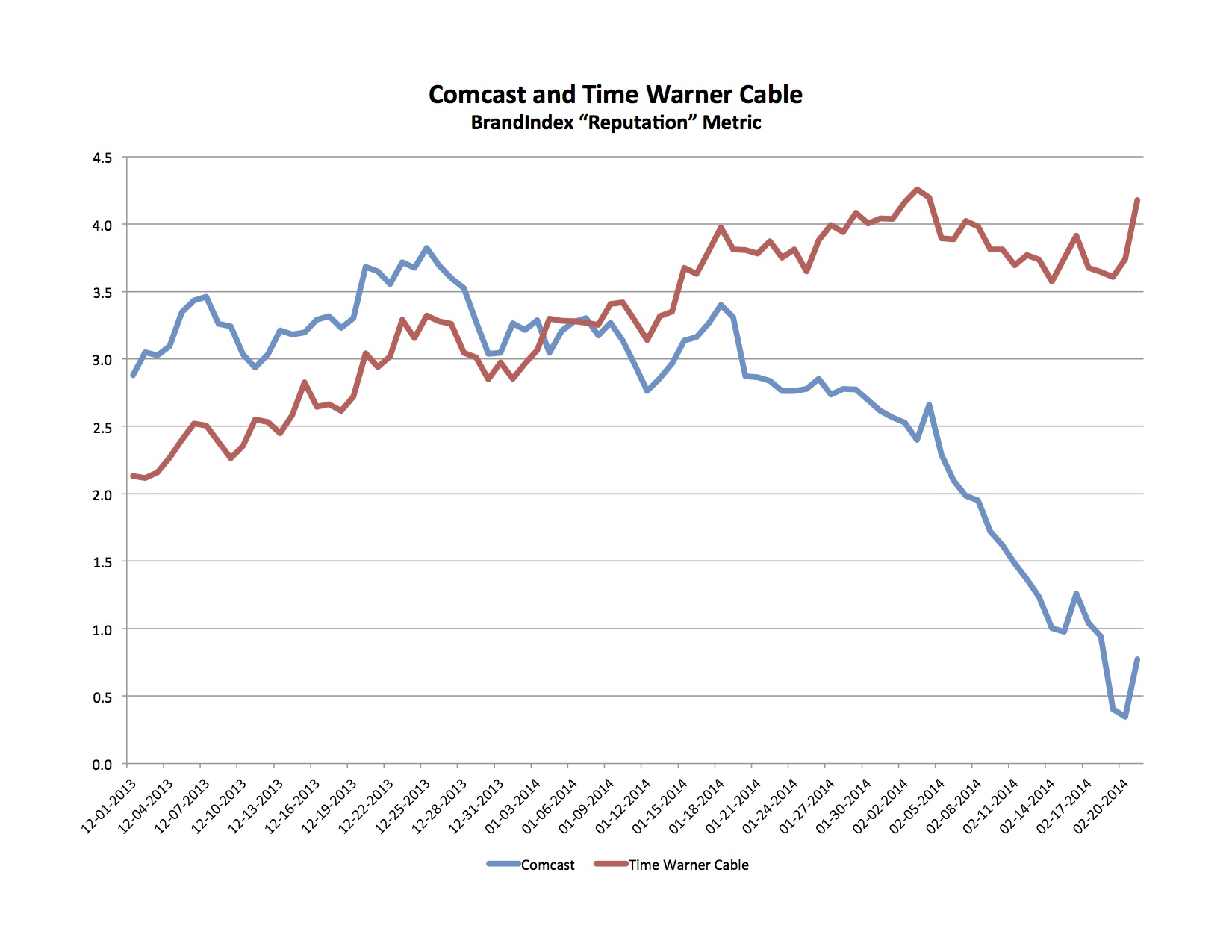

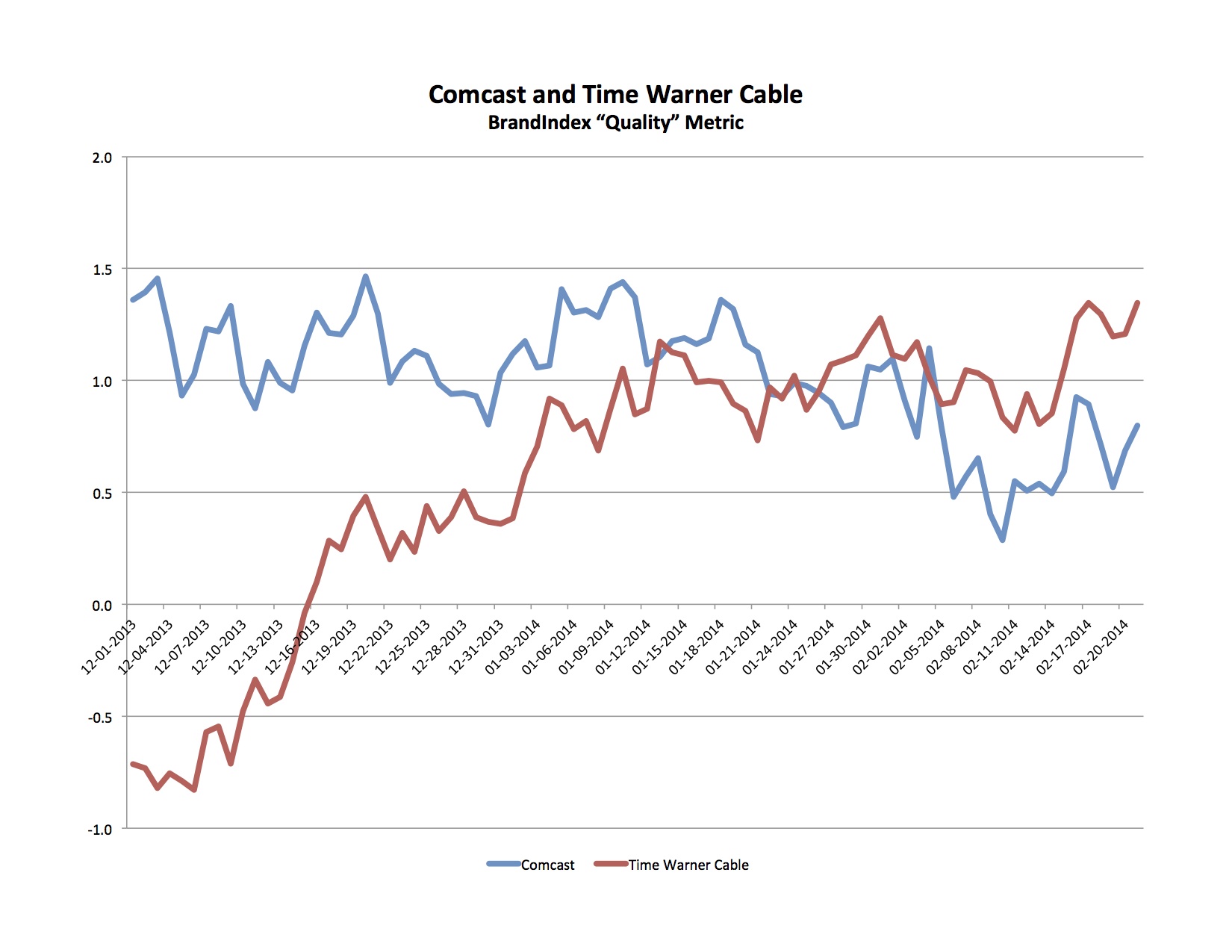

This, however, is a sweetheart deal for Time Warner Cable who has struggled for years to be seen as a company that provides consistent, high-quality service to its subscribers (which it doesn't). Recent polling conducted by BrandIndex (a subsidiary of YouGov) shows some interesting things.

As one would expect, Comcast's "reputation" and "satisfaction" metric falls sharply, but in an interesting turn, Time Warner Cable's metrics sharply increase.

So the acquisition is good for Time Warner, but has the opposite effect on Comcast. But it doesn't matter since, as Gigaom mentions, it's all about the broadband and its associated revenue stream:

According to UBS estimates, the combined company could see its consumer data-only revenues go from $17 billion at end of 2013 to about $23 billion by end of 2018. Voice revenues go from about $6 billion at the end of 2013 to $6.6 billion at end of 2018.

Really. Who cares if I am a happy subscriber -- just make sure I continue to pay.

Netflix had to pay Comcast in order to protect high-quality streaming - there was no other way to ensure that the content, for whom Netflix has begun designing around the viewer, makes it into the home.

It is critical that Netflix's content be delivered: it retains customers and makes the comany money. Netflix is starting to see that it has reached the innovators, early adopters and early majority and is starting to flatten in growth (or at least it is attempting to think about the very near future when that happens). It is a public company and needs to ensure that it's cash flow remains robust and that it can grow its market capitalization and attract investors. in order to do that it needs to innovate; House of Cards was just that innovation it needed as a proof of concept. Since the first season aired in 2013 (and was announced in 2012), Amazon has also gotten into the content creation service releasing Alpha House, Betas and, a whole slew of new shows in 2014.

So what does "House of Cards" tell us about what is actually going on in the content creation and content distribution industry? Well, unlike today's ability to binge-watch a season or two of a show, I guess you will just have to tune in later and find out.

It All About MY Health

If you think about it, health is a fairly selfish thing. Not that it is not a bad thing: bring healthy allows you to climb that mountain, go to work and make a difference and be a hero to your kids. Further, we also care (selfishly) about the health of those around us: family, friends, colleagues since they are possessive to us (my family, my friends and my colleagues)

But are we turning our altruistic health "selfishness" into more of a self-important "fetish"?

Looking at the graphs below we are able to see that global searches for the term "my health" are increasing, whereas the search term for "health is decreasing"

Specifically, total volume of searches for "My Health" are increasing, and quite quickly I might add (30% YoY), where searches for "health" have decreased -13% YoY.

Also, you can also see in the charts below that geography places a role. "My health" is searched primarily in the global North, and "health" is searched for in the developing, global south. Sure, there are crossovers, but the core of these searches are geographically opposed.

Total volume of searches for "My Health"

Total volume of searches for "Health"

This analysis is not a scientific study. There are variables that I did not control for such as alternate searches, growing trends and the like. I am trying to make a point that is more broad: Are we caring about our (collective) health in a - well - healthful way?

The multitudes of topics like the quantified self, new diet fads (South Beach, Paleo and cleanses) and workout regimes (crossfit) are all channels through which enterprising companies can sell their you their products, services and pop culture. But, do they work? Are they able to make humanity more healthy, are they dealing with the basic health disparities that exist locally, nationally and globally?

The most critical thinking about our well-being should be that that changes our fundamental relationship with it: a selfish health relationship. Meaning that one no longer relies on the screens, apps and gadgets purchased as an alibi for healthy living -- in any other situation that is a lie.

For all the good "selfish" products out there, I submit that there are en equal number of "self-important fetish" products to match. These fetish products don't advance our fundamental thinking of health, or even motivate us to do/be/think in more healthful ways; they exist simply to make money, burn resources and milk our wallets and (to reference the graphics from above) to help us avoid the human condition outside of our own bubble (and THAT is self-importance more so than selfishness).

So what are we to make of this? I don't have an answer; just a question for us:

"How selfish are you?"

Behavioral Economics and the Advertising Craft

Turns out advertising isn't all about easels and boards.

I was reading an article in Forbes which discussed the overall opportunity marketers have by tapping into behavioral thinking; it got me to thinking:

From economists long dead

Too long the marketing and advertising profession has works along side creative alchemy and mathematical voodoo. In the past decade there has been a strong push to better understand the voice of the consumer, run models that enable brands to better price their wares and let marketers better push through the value proposition in an enticing and buzz-worthy way.

As the article points out, Adam Smith, godfather of 18th century political economic thinking (remember The Wealth of Nations? The invisible hand?) and 20th century Irving Fisher (Utility theory) and Vilfredo Pareto (Pareto principle, or the 80-20 Rule) believed that human psychological engagement in rational decision making could negatively impact the economy, not out of malice, but because the human psyche is a subjective beast. And due to its subjectivity, naturally academic theorists believe that it is a problem with a solution. Is it?

From the human mind, with love

Nassim Taleb (of Black Swan fame), along with contemporaries like Laurie Santos and Paul Dolan, believe that the human element in rational economics is something that can be studied, isolated and, perhaps, extracted.

Ultimately the thinking comes down to looking at patterns, process and decision analysis. But does this get to the heart of the human decision, or is this a study that better illuminates the structure in which these decisions are made? If a starving man is presented with a bowl of Brussels sprouts (and let us say he hates Brussels sprouts), he will invariably eat them. the situation dictates the outcome, but not the deeper human motivation. This is a simple problem, but one that behavioral economics (and indeed advertising) must pay attention to. Controlling for externalities and biases is not as simple as it may seem, but a broad set of data and information must be collected, sampled and analyzed.

And...?

Behavioral studies are helpful, but not if they are conducted in a vacuum. Big data, social meta data mining, systemic consumer purchase information, macroeconomic indicators, global news and media and other stimuli are all factors in gaining the edge in getting closer to the customer and understanding (better understanding) how they think and what motivates them.

If advertising and behavioral sciences are closer aligned the potential can be quite lucrative, and altruistically, a winning proposition for all vested partners (consumers, marketers and brands).